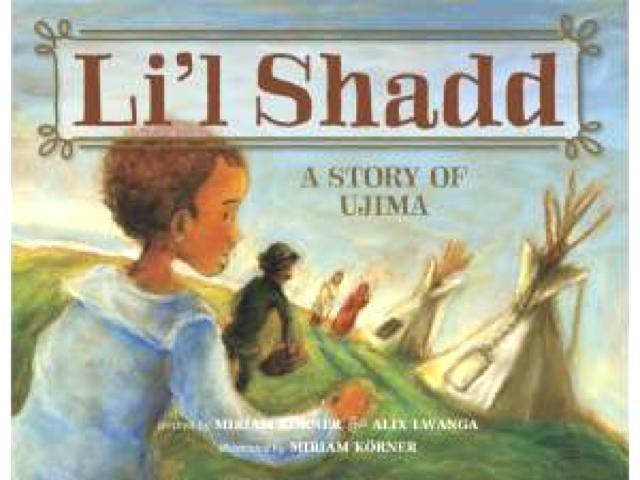

“Li’l Shadd: A Story of Ujima” is written by Miriam Körner and Alix Lwanga, and illustrated by Miriam Körner. It is published by Your Nickel’s Worth Publishing. This review is by Shelley A. Leedahl

Saskatchewan’s history is so multi-culturally rich that there are, admittedly, elements of it that I’ve scarcely even considered.

Take, for example, the first African-Canadian pioneers, including the trail-blazing Dr. Alfred Schmitz Shadd (d.1915), for whom two Melfort streets and a northern Saskatchewan lake are named.

Dr. Shadd shared an affinity with First Nations’ folks, “due to the similarity of their experiences with colonization and racism,” and the Saskatchewan African Canadian Heritage Museum — with the assistance of other funders and sponsors — has brought just one of Shadd’s success stories to light in the delightfully-illustrated children’s book, “Li’l Shadd: A Story of Ujima”.

The title character, Li’l Shadd, represents Garrison Shadd, the real-life son of the good Dr. Shadd, who’s also recognized for his work as a politician, teacher, farmer, journalist and friend.

Garrison was actually five years old when his pioneering father died, so the story itself is slightly fictionalized. The plot concerns the child accompanying his father (via horse-drawn wagon) to tend to the baby girl of a local First Nations’ family who lives in a tipi near Stoney Creek.

This medical emergency coincides with Li’l Shadd’s birthday, and the boy is remiss that it will interfere with his party.

His father explains that he must treat the infant girl, as he is the only one who is able to, and the African philosophy of Ujima (a Swahili word that refers to “Shared work and responsibility,” and the idea that “our brothers and sisters concerns are out concerns”) is referred to.

There are crossovers with real life here. Garrison Shadd also had a baby sister, and when the sick child in the story is healed, her father, Nékénisiw (Cree for “He is foremost, he leads”) plays a drum not unlike Dr. Shadd’s African drum, and thanks the doctor in Cree and English. Three of Nékénisiw’s children were actually treated by Dr. Shadd in the 1890s — a fact derived from Melfort-area settler Reginald Beatty’s diary.

This uplifting and historically-relevant story celebrates family, community, and culture, and illustrates how even children are able to grasp the selfless concept of Ujima, which is one of seven important Kwanzaa (an African holiday) values.

Personally, I can’t think of a better way to teach history and get a positive message across than by presenting it in a full-colour picture book.

Körner’s culturally-sensitive illustrations spread right across the page, and this “full bleed” style helps keep one sealed under the story’s spell. I appreciated the suggestion of floral bead work on Nékénisiw’s vest, and the baby’s homemade rattle. Even more so, I celebrate the mutual trust and respect the characters display for each other, and for each other’s cultures.

This Special Edition legacy project is beautifully rendered, and I hope it is widely read.

Teachers may wish to consider sharing “Li’l Shadd: A Story of Ujima” during their schools’ multicultural celebrations, and to make it extra inviting, a teachers’ guide is available at www.sachm.org.